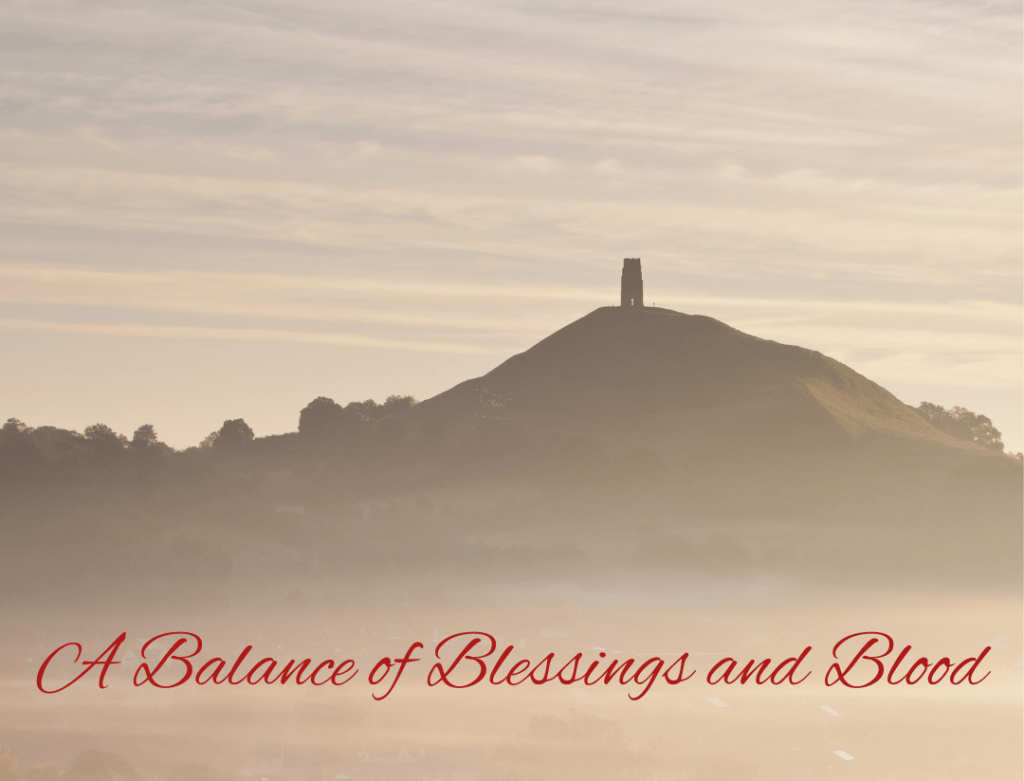

I wrote this short story for consideration for inclusion in an anthology about Morgana le Fey. Alas, it was not accepted, but I am quite fond of it and so decided to share it here. Let me know your thoughts!

I opted to write about a version of Morgana as described by Geoffrey of Monmouth in his narrative poem, Vita Merlini, which was published in 1155 AD and was the enchanting figure’s first appearance in literature that is currently recognized. Her name is given as Morgen in that work, and so that is how I chose to refer to her in my story.

The sea swells and surges up the shores of Avalon. The swash rises through the air in a spinning rush of water, forming an aqueous column that coalesces into the form of a naked woman. The figure solidifies in a gradual progression from the bottoms of her bare feet to her water darkened tresses.

Morgen has returned home.

Her sisters have been awaiting her arrival. Glitonea, taking her turn as lookout, approaches with a robe held open before her. “What word?” she asks as she wraps the garment about her eldest sister’s shoulders, which are glistening with water droplets and adorned with gooseflesh.

Her lips pressed into a thin line, Morgen looks to Glitonea and gives a bare shake of her head. The news is grim.

But she is surprised to see that beyond a brief furrowing of the brow, her sister does not seem as dismayed as she might. Morgen realizes that the Glitonea is harboring news of her own, and it is something that has her excited. She waits for the other woman’s storm colored eyes to meet her own.

“What is it?”

“Men have come to the island.” The words are expelled in a rush.

“Men?”

“Mortals.”

Buffeted by the bracing sea air, Morgen pulls the ends of the robe tightly around her body and gazes up at the tor that juts up from the coastline while considering this news. After a moment, the two women begin the trek up the cliffside path to the keep, the home they share with their seven other sisters. Glitonea soon breaks the silence.

“Did you really find nothing?” she asks in a faint voice.

Morgen did not find nothing. Her travels through the seas took her to Greece, where she found a dragon with no less than one hundred heads thwarting her efforts to seek a meeting with the Daughters of the Evening. She found waters in Europe that restored sight, waters that drove its drinkers mad or bestowed great strength. She had been soaring over yellowed plains when through the air came to her an albatross’s cry resonating in such torment that her own wings missed a beat and her heart dropped in her breast. She had encountered a species of bird that brings forth life through the shedding of its own blood, a sacrificial offering of balance.

What Morgen did not find was an answer to how to stop the golden apple tree at the center of Avalon from continuing to wither and die, and with it the island’s magic.

The boons of the Fortunate Isle are tied to that singular tree with its resplendent fruit. Its roots feed enchantment into the soil, sending its gifts outward through its communion with the rest of the land. It is thanks to this tree that Avalon is so fruitful of its own account, without need of plough or toil. For its devoted inhabitants, the land provides without fail the fruit and grains that feed them and the herbs they use in their healing balms, unguents and tonics. It is the exceptional nature of the place that grants the sisters that call it home the alacrity and ease with which they have been able to focus and enhance their spellwork. Their conjurations are threefold as strong as they would otherwise be.

And now it all decays. Over the past months an insidious rot has taken hold, the effects of which have been subtle as of yet, but worrisome all the same.

“Nothing of use. At least not that I can see,” Morgen answers. As they climb the wooden steps to the elevated entrance of the keep, she says, “Tell me of these men.”

Glitonea obliges gladly. “At first we thought it was just three of them, two warriors in hauberks and a man dressed like a bard, all ferried by Barinthus on his barge. But as they came ashore we saw there was another man, wounded, laid out on the deck.”

“You offered healing?” Morgen asks. What she really means is, were you able to heal the man, or have your abilities deteriorated even too far for that?

A look of consternation steals over Glitonea’s face as she explains, “We each of us tried. But you have always been the most skillful healer among us. Perhaps you will succeed where we have not.” Then, somberly, “It is a most grievous wound.”

Crossing through the eastern solar of their home Morgen sees more of her sisters, some alone and others arranged in groups. Save for Thitis, who is drawing doleful music from a cither, her favored instrument that she has not found the will to take up much in the past months, they appear to stand or lounge around purposelessly. They have been thrown from their routine with the arrival of strangers and do not know quite what to do with themselves. One of them lets escape a titter and Morgen glances over her shoulder to look for the source. Moronoe and Tyronoe are leaned in close conversation with one another before a tapestry depicting a stag posed within a ring of hazel trees. The former holds a hand clasped over her mouth. It is unsurprising to Morgen that those two, despite the grave manner of the men’s visit, would yet be delighted by their presence. The opportunity for social exchange outside of their circle appeals to many of the women, of course, but there are those who are especially enamored with the potential for commerce of the sexes. There are also those who will have been disappointed that the ferryman had not brought them fresh female company.

As she exits the room and approaches the keep’s central staircase, Morgen tells Glitonea, “I will go to my chamber to dress. Then I will see to these men.”

Standing in her bed chamber and dressed now in a sleeved undergarment, Morgen plaits the damp tangle of her hair with a deft hand. She slips into a dark green peplos, fastening it at the shoulders with brooches. All the while her mind is a churning maelstrom.

There had been seasons of Morgen’s life when mortals coming ashore would have appealed to her foremost as an opportunity for exercises in love. Such activities held little interest for her these days, and not only because she has tired of partners scorning their beloved the moment they grow bored, all lovers feeling jilted in the end. If one of the paramours is skilled in enchantment, well, the accusations flung become all the more absurd.

But now. The golden apple tree waning for the first time since the sisters had made the island their home decades before, and Avalon’s magic with it. The ill portent of the albatross’s lament. And now the arrival of mortals. What did it all mean? Had she missed some sign writ in the stars? Had her skills reading the heavens diminished so much?

From the cabinet beside her bed, Morgen pulls out a corded belt to cinch around her waist. From one side she hangs a pouch of herbs, from the other a ceremonial blade in its leather sheath. Before shutting the cupboard door, something catches her eye. On the floor, half hidden behind her slippers, is the drinking horn she had once spelled. The charm she laid over the instrument was designed to reveal infidelity by causing any unfaithful lover who attempted to drink from it to spill its contents without a single drop passing his or her lips. For many days and nights she had struggled to perfect the magic. Finally, she learned that in order to force a person’s secrets into the open in this way required her to divulge one of her own. Only after speaking her greatest shame into the mouth of the vessel would it perform as intended. This took further consideration on her part, as Morgen is a woman who does not involve herself overmuch with the concept of shame. Just as she feels an entirely changed being from the one she was at the time of the horn’s creation, she feels no antagonism for that woman of the past; some of her actions may have been misguided, but her feelings then were just as valid as her desire to restore Avalon’s glory now.

Toeing the horn further to the back of the cabinet, she shuts the door and goes to see about healing a wounded man.

The prostrate form has been laid out atop the golden coverlet over Tyronoe’s bed. His chain mail and greaves have been removed, leaving him stripped down to tunic and breeches. His brow is furrowed and his mouth twisted in a grimace, but his eyes remain closed; he has withdrawn into himself. Blood-covered hands are crossed gingerly over the black stain spread over his abdomen, an unconscious guarding of a wound that draws the eye like a baleful storm cloud on the horizon.

Arrayed around the bed are those who accompanied the injured man to the island as Glitonea has relayed. One of the soldiers has yellow curls, the other brazen eyebrows and a beard halfway to gray. The bard doffs his cap and falls to his knees before Morgen where she stands next to Glitonea just inside the threshold.

“Great Lady! I am called Taliesin. These good men of Caerleon are of the king’s retinue. You, Lady, are renowned across the lands for your great skill in healing ailments of all kinds, your talents said to be matched only by your wisdom and beauty. We come to beseech you: please, do what you can to save the life of the Benevolent and Wise King Arthur!”

Halfway during this speech, Morgen had returned her eyes to the figure on the bed. The man Taliesin remains kneeling on the floor as he awaits her response. Morgen turns her head slightly in her sister’s direction and speaks in a soft undertone. “You did not say he was a king.”

“Does it matter?”

Morgen crosses the room in measured steps, approaching the bed. “How did he sustain this injury?” she asks. The bard struggles off his knees to stand behind her.

“Run through with a sword wielded by his own nephew,” the younger of the soldiers answers. He glares through his curling locks as he speaks these words, but Morgen knows his animosity is directed at this nephew, not at her.

Stopping at the bedside, she continues to assess the sight before her. The muscles of the king’s throat work as he labors to swallow what moisture his body is able to muster, eyes still screwed shut. Eventually she shifts her scrutiny down toward the gash in his belly. She begins to reach a gentle hand toward laceration when she is surprised to find the man’s own suddenly gripping her wrist, more strength in his hold than she would have thought he was capable of summoning in his current state.

She looks up and finds his eyes open and staring into hers. She notices they are green.

Silence commands the room for several long moments while they observe one another. Finally one of his soldiers ventures, “My Lord King?” Arthur’s grip loosens until he eventually drops his hand to his side, but his eyes remain open. He does not speak.

Morgen returns her attention to the wound. It is not a clean cut, but jagged as though his opponent had wrenched the steel in a twisting motion before tugging it free. It seems a cruel act born of a singular enmity. She lets her fingers hover over the rent in the flesh and extends her senses, confirming what she has already begun to suspect.

It is too late to save this man. The injury is a grievous one, yes, but his body’s reaction to the insult has passed the point of reversal, birthing a cascade of further catastrophes throughout his systems, setting a multitude of fires that cannot all be doused before he succumbs. Looking at the man’s face, Morgen sees he has shut his eyes once more, and notices now the gray shadow that has begun to tint his skin. She imagines he does not have much time left.

To the side of this throat she can see the fluttering of a pulse, the blood yet coursing through his veins, albeit more feebly than usual. The blood of a king. The eddies within Morgen’s mind swirl with a new turbulence as she considers this.

“I have heard of you, Arthur of Pendragon,” she says. She believes he can still hear her, though he makes no response. “You are known to have united the peoples of your land. It is said you champion equality among your advisors, allowing no unfair advantages due to birth or other circumstances left to fate alone. You treat all persons with respect without requiring them to earn it, but rather allowing them the agency to lose it by their own efforts. You have been found worthy across varying fields. You, Arthur, are a Great King.”

She hears one of the other men choke back an expression of grief. It does not do to weep or otherwise conspicuously convey sorrow before a death has occurred, as it may draw the attention of forces from the Otherworld that would only hasten that outcome, even if it had not been an inevitability.

Morgen takes a moment to arrange her face before lifting it to address Taliesin. “You must leave him here with us. His recovery is not a thing that can be managed in a short time.”

It is as though a flame has been lit within the bard, the way his face lights up at these words. “You can heal him, then!” he cries. Morgen makes no answer. “Yes, yes, we will leave him in your capable hands, Lady. Your divinely appointed skills cannot be rushed, we understand! No motte and bailey is raised in a single day.”

Morgen nods and then resumes her position next to her sister. They watch as the men huddled around the recumbent form in the bed, taking their leave of their lord and speaking their reassurances and pledges to him. The women see tears of relief upon the younger soldier’s cheek. They and several other of their sisters walk the men down to the beach, where Barinthus is already waiting with his barge, as he is always aware when his services are needed. The bard continues to effuse gratitude and praise even as the vessel pushes off from shore.

Some of the women pull away and return to the keep. Morgen and Glitonea remain the longest, watching the forms of the departing mortals recede along the bobbing waves.

“You let them believe we would heal him,” Glitonea remarks after several long moments.

Morgen swipes away strands of hair that the wind blown in off the sea has stuck to her lips. “They heard what they wanted to hear,” she demurs.

“What you wanted them to hear,” Glitonea amends. Morgen makes a swift tilt of her head as if to say: these things are the same. “What is it you are planning?”

Looking her sister full in the face, Morgen explains. “You asked if it mattered that he is a king. In calling himself a king, a man dons a mantle of importance like a cloak, granting himself a significance that may not have been there before. This consequence goes beyond surface level. He is changed in ways he may not have anticipated.”

Glitonea stares out to sea, considering these words. In time, Morgen says, “Help me gather the others. We will need a litter to convey him.”

The nine sisters stand in Avalon’s central grove, arrayed around a dying man laid beside an apple tree. The tree is also dying.

The browned edges of shriveled leaves curl inward. The golden fruit is wrinkled and dull. Usually while standing in this orchard there can be heard a low, sonorous tone that seems to originate in the earth itself. Always faint, the sound is now nearly imperceptible.

Thitis kneels on the ground with the man’s head and shoulders laid in her lap, holding him tilted slightly so that he is angled toward the tree. Had he been aware of his surroundings, perhaps a hope that the women were about to feed him one of the golden apples said to grant immortality would have flared within his chest. Yet he is heedless. Before transferring him to the litter to bring him to the tree, Morgen had tipped one of her draughts into his slackened mouth and induced him to swallow. His brow had soon smoothed and he now slept the peaceful sleep of the untroubled, pain nothing more than a bad dream from which he had moved on to sweeter visions. It was not his suffering Morgen sought; she was not a monster. In fact, she found herself wishing for a moment that she had had the chance to meet the man before fate had come calling on him. Her words before had been sincere. The deeds he was known for were mostly cause for great admiration, although ruling a kingdom was never a bloodless endeavor.

They would drop his armor into the sea, after, as an offering, and in supplication for his safe passage to the Otherworld.

Morgen lowers herself to her knees before him.

“Sisters,” she calls out. “For decades the magic of Avalon, spawned from this very spot, has provided life to the island. Sustenance. Restoration. Knowledge and guidance. But in all things, there must be a balance. The magic is owed its due. What can we offer as equipoise for these gifts?” She looked at the others, all standing with their heads held high, except for the kneeling Thitis, who stroked the man’s hair. Morgen slid her blade from its sheath on her belt and answered her own question. “We offer the death of a king!”

In one sure motion, Morgen glides her blade in between King Arthur’s ribs and upward into his heart. She withdraws it and Thitis tilts him further, so that his heart’s blood pumps directly onto the earth housing the tree’s roots.

The women all begin wailing, their keening sending birds from the surrounding foliage into startled flight, as the golden apple tree unfurls verdant leaves, its fruit plumpens and gleams, and the earth sings.

Avalon lives.