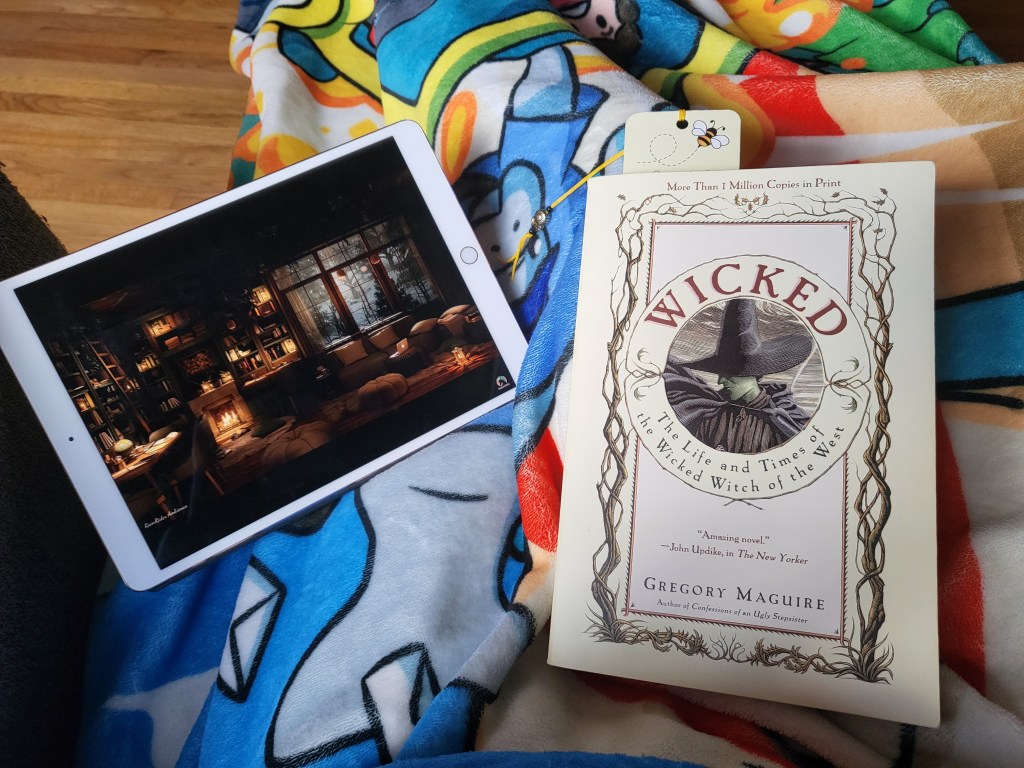

Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire is 406 page novel published in 1995 by ReganBooks, and is the first in The Wicked Years series.

Genre:

Fantasy, Retelling

Opening Line:

A mile above Oz, the Witch balanced on the wind’s forward edge, as if she were a green fleck of the land itself, flung up and sent wheeling by the turbulent air.

My Thoughts:

Oh, this book–I wanted to live in its pages forever!

I can certainly see how this book would not be every reader’s cup of tea. It is not a fast paced, action packed, plot driven narrative. The writing is very literary in style as readers are planted in the world of Oz and learn of its cultures, religions, and politics through the lens of one woman’s life story. But the writing is also absurd and humorous at times, surprising laughs out of me when I wasn’t expecting them. The five Parts of the story follow different eras of Elphaba’s life, each section taking place several years after the previous one. Through her life story we confront questions of morality, faith, and philosophy. And though it fell apart a bit at the end for me and left me with many questions, I loved every minute of my time spent in Maguire’s Oz! (To be clear, I definitely would not want to LITERALLY spend time there.)

In Part I, Munchkinlanders, we meet Elphaba’s parents: Frex, the unionist minister, and Melena, often left alone at their remote cottage to console herself with mind-altering substances. Frex is on a mission to preach against tiktokism and the pleasure faith that is becoming more popular when Melena gives birth to their first child, who is born shockingly green of skin and with razor sharp teeth (and because the author seems to be rather fixated on male genitalia in this first part of the book, she is born with “a bit of organic effluvia” or something in her groin that makes the midwives argue at first over whether the infant is a boy or a girl). She also avoids water at all costs, as it seems to pain her. Frex and Melena believe this child is meant as a punishment for them, or perhaps that she is possessed by some devil.

Perhaps, thought Nanny, little green Elphaba chose her own sex, and her own color, and to hell with her parents.

When Melena is expecting again, she faithfully takes capsules provided by Yackle, a crone at an alchemy shop, to try to prevent a recurrence of the defects of her first child (instead, little Nessarose is born without arms). In the reading of tea leaves, Yackle predicts greatness for Melena’s children, two sisters.

“She said history waits to be written, and this family has a part in it.”

In this part of the story we also get introduced to the Quadlings of southern Oz, as Frex and Melena befriend a foreigner named Turtle Heart. Quadlings seem to be seers of some sort, and to be the only residents of Oz who are aware of our/Dorothy’s world. Quadling Country is swampy land where the people build their homes in the trees, connected by platforms secured with ropes. Workers from the Emerald City have begun to build dikes and divide the land into parcels that will no longer be self-sustainable, and then they find the land is rich in rubies. The Quadlings have foreseen a cruel and mighty stranger king arriving in Oz via hot air balloon, exterminating them in order to pillage their land for its riches. Frex decides this means the population down south are more in need of his ministrations, and he sets off with his pregnant wife, toddler daughter, and Quadling friend in tow.

“She is herself pleased at the half things,” Turtle Heart said. “I think. The little girl to play with the broken pieces better.”

In Part II, Gillikin, 17 year old Elphaba is off to university. She winds up befriending her pretty roommate, Galinda, which could not be more of a surprise to either of them.

Galinda was slow coming to terms with actual learning. She had considered her admission to Shiz University as a sort of testimony to her brilliance, and believed that she would adorn the halls of learning with her beauty and occasional clever sayings. She supposed, glumly, that she had meant to be a sort of living marble bust: This is Youthful Intelligence; admire Her. Isn’t She lovely?

Galinda does not understand why Elphaba spends so much time reading old sermons about the nature of good and evil. Pagans of yore believed evil originated with the vacuum created when the Fairy Queen Lurline, who they considered to be the the creator of Oz, left them: “When goodness removes itself, the space it occupies corrodes and becomes evil, and maybe splits apart and multiplies. So every evil thing is a sign of the absence of deity.” But the early unionists argued evil was an invisible pocket of corruption floating around, “a direct descendant of the pain the world felt when Lurline left”, and anyone might pass through it and become infected with evil by no fault of their own.

“But they believe in evil still,” said Galinda with a yawn. “Isn’t that funny, that deity is passe but the attributes and implications of deity linger-“

“You are thinking!” Elphaba cried.

During her time at this institution of higher learning, Elphaba becomes aware of the growing discrimination, encouraged by the laws passed by the Wizard of Oz who had usurped the Ozma Regent years before, against Animals (anthropomorphized, sentient and speaking versions of lower case A animals). One of their professors, Doctor Dillamond, is a Goat researching the biological basis for what makes an animal different from an Animal and from a human, to disprove that Animals are lesser and stop the inhumane treatment of those who had, up until the arrival of the Wizard, been considered equal members of society. It is during this time in her life that Elphaba learns her righteous indignity, a spirit of activism, and her derision for political machinations. This part of the story includes a murder, and a bid to recruit Elphaba, Glinda (who has changed her name for reasons I can’t explain without spoilers), and Nessarose into the service of the despotic Wizard. His Oz is “a seething volcano threatening to erupt and burn us in its own poisonous pus”, with “communities on edge, ethnic groups against one another, bankers against farmers and factories against shopkeepers”. The one attempting the recruiting assures Elphaba she can harness her spirit and she “needn’t live a life of unfulfilled rage”.

Also, an old woman named Yackle works selling tickets at some questionable sex club.

In Part III, City of Emeralds, we see Elphaba’s time as a secret agent, an underground activist. It is also when she carries out a romance with Fiyero, and I find I have to comment on his character here. I have never seen the Wicked musical, but I see that in the upcoming version, Fiyero is played by Jonathan Bailey, who seems lovely. I am a bit confused by this casting, though, as the character of Fiyero is an Arjiki prince from the Vinkus to the far west, a dark-skinned man with blue diamond tribal tattoos over his entire body. He is described as dark-skinned multiple times, ochre-skinned, and one character observes that his skin is the color of shit (this book is all about prejudice and discrimination in “civilized” society.) So why is he played by a white dude?

Also, Fiyero is kind of the worst. All he does is patently disregard and disrespect all of Elphaba’s clearly expressed wishes, so I don’t understand the romance between them at all. But he does allow for conversations with Elphaba about the ethics of her righteous campaign and the eschewing of personal responsibility for any collateral damage. There is talk of terrorists hiding behind their ideals, and when questioned about the chance for innocent bystanders to be caught in the crossfire, Elphaba goes so far as to say, “Any casualty of the struggle is their fault, not ours.” This is also when we first hear about Elphaba questioning the existence of souls, and that she certainly does not believe that she herself is in possession of one.

After some more murder, we find ourselves in Part IV, In the Vinkus. At the end of the previous section, Elphaba arrived at a mauntery (a convent) in a state of “dreamless, sleepless grief” and is welcomed by a decrepit old woman, mad Mother Yackle. Seven years later, it is time for Elphaba to finally leave the mauntery “to conduct an exercise in expiation”:

“You feel there is a penalty to pay before you may find peace. The unquestioning silence of the cloister is no longer what you need. You are returning to yourself.”

Elphaba joins a caravan headed into the Vinkus accompanied by Liir, a young boy raised among the orphans at the Cloister of Saint Glinda. They travel to Kiamo Ko, the seat of the royal family of the Arjiki, where Elphaba plans to seek forgiveness from Fiyero’s wife, Sarima. But Sarima will not hear of it:

“You want to throw down your burden, throw it down at my feet, or across my shoulders. You want perhaps to weep a little, to say good-bye, and then to leave…This is my home, I am a nominal Dowager Princess of Duckshit, but I have a right to hear and I have a right not to hear. Even to make a traveler feel better.”

There is more talk evil and good (“in folk memory evil always predates good”), and there is the question of who Liir’s parents are or were (I felt so bad for that little boy!) But Elphaba will not leave Kiamo Ko without being forgiven for what happened with her and Fiyero, and so she and Liir over time become part of the household and family. During this time, Munchkinland secedes from Oz.

In Part V, The Murder and its Afterlife, things have not been going well for Elphaba. Now her sister (who had come to be viewed as a religious tyrant) has been killed be a house falling from a tornado, and some foreign girl has the magic shoes that Nessarose had promised would be Elphaba’s if she were to predecease her. The Wizard and Elphaba each have something the other wants. There is more talk of Yackle, the Kumbric Witch of legend, the Clock of the Time Dragon, the Other Land, souls, good and evil, parentage. Who is in thrall to whom? And it all comes to a head in an ending we are familiar with from the Wizard of Oz, albeit through a different perspective than that told by the victor of the story.

What I didn’t love about this last part was that Elphaba here hardly seemed recognizable as the Elphaba in all the rest of the book. So I couldn’t really understand her motivations here. Some reviewers describe it as her descent into madness, so I guess that could explain it. But boy did I enjoy the journey getting to this point, and I think this book presented me with things I will be thinking about for a long time.

Maybe the definition of home is the place where you are never forgiven, so you may always belong there, bound by guilt. And maybe the cost of belonging is worth it.

I think I MUST read the sequel at some point, since people seem to say it answers some of the questions left by this book. I look forward to it!

People who hated this book seem to primarily have picked it up either under the belief that it would be like the Broadway musical, which it apparently isn’t (and now I’m wondering if I really want to see the movie version of the musical after all, since I loved the book so much and will probably be disappointed by how different the movie/musical is), or under the belief that it was a children’s book because the source material it is reimagining was for children. So be aware: the musical based off of this book apparently takes liberties and does not follow it precisely (this grim story also seemed like a very odd choice to turn into a musical, to me); and this story explaining everything that Elphaba went through to shape her into the Wicked Witch of the West painted as the villain is most certainly not for children.